Kennedy’s article

IT'S YOUR PROBLEM NOW, KIDS!

Finding Space for Queerness:

Reflecting on the Impact of Lost Spaces

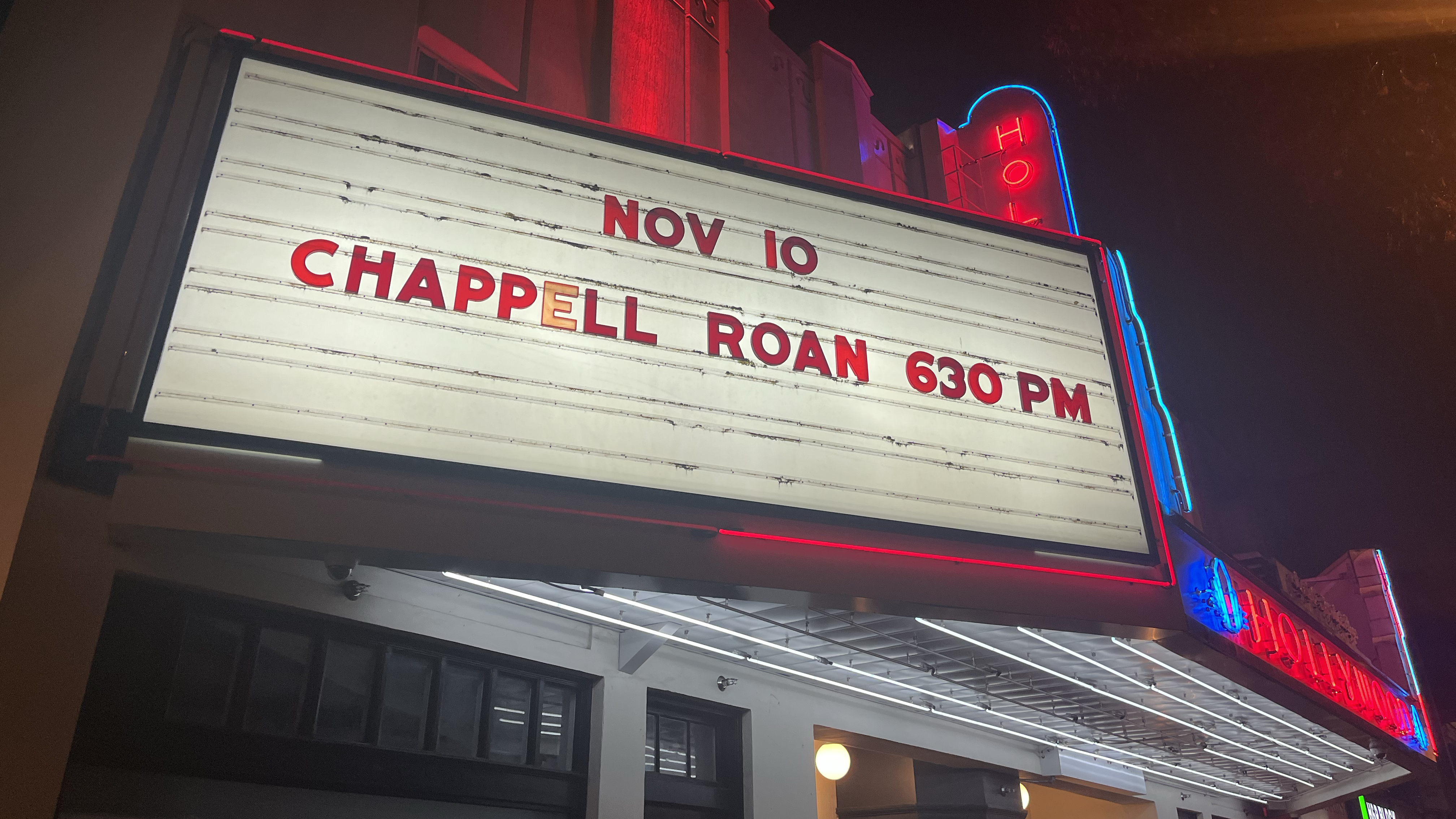

Taken inside the Hollywood Theatre, dated November 10th, 2023. Photo: Kennedy Halwa

A Note From The Author

Consider this piece memoir-ish, a near-obituary, and a history of. May queer youth find (queer) joy, comfort, and safety simultaneously for years to come.

Heavy subject matter regarding queer history will be discussed. Take care when reading.

Kennedy Halwa

In my 22 years of life, there has only been one evening in which I felt truly and entirely safe being out in public as a queer person. This was in Vancouver, last October, at a Chappell Roan concert. I went with my roommate, their girlfriend, and the girlfriend’s roommate— three friends I’ve met through my degree, all of us sharing in queerness in some way. (I consider myself “out-ish”— which is to say only really in Victoria, my second home, not as much in my Albertan hometown.)

Leading up to the concert, I was able to soak in my queer identity and all that comes with it. We spent hours in thrift stores, finding tartan skirts and silky slip dresses and sheer tops, all in colours far from our own wardrobe’s palettes. I experimented with the new colourways within the four walls of my home, but I remember not being sure if I’d make it out the door with the colours on display.

We arrived at the girlfriend’s roommate’s family home day of, a couple hours before the concert. After napping to recharge, out came the glittery makeup palettes, the hot hair tools, the moisturiser, the neatly folded, pre-planned outfits. In a crisp white bathroom with two sinks and a long mirror, big enough for four smiling faces to fit into, we four barely twenty-somethings forgot we were even on a ferry that morning.

I danced around in my bralette and flared jeans and forgot how I felt at 12 years old, awkward and anxious at the popular girl’s sleepover birthday party. Here, I wasn’t left out of conversations, I didn’t have to worry if I brought the “right” pajamas. Instead, I was the chosen D.J. for the weekend, rotating early 2000’s hits with whatever I was listening to at the time, plus songs I knew we’d all be familiar with. Between “Fergalicious” and Taylor Swift, we took turns dancing and laughing. Somehow, as the nerves fell away and my nervous inner child quieted, I borrowed one of the other girl’s eyeshadow palettes and tried on coloured eyeshadow. It wasn’t something I had worn before, or thought I could ever pull off. But, astoundingly enough, the bright yellows and greens complimented my hazel eyes. The girls approved.

I remember being so nervous in my borrowed highlighter-esque crochet shrug and jeans, with stick-on pearls at the corners of my eyes. I remember thinking, with the crown of my hair in two high pigtails, that my younger self would be in disbelief. She would be astounded that I would willingly wear something with pink tones. But, I think she would also think I am cool.

Outside the Hollywood Theatre, Vancouver, BC. Photo: Kennedy Halwa

In the evening, we walked up to a venue with neon lights and a marquee sign, announcing the event of the night like it was greeting us personally. We knew we were in the right place by the abundance of multi-hued outfits and line up of beaming faces. Some with cowboy hats or flower crowns, some with dyed denim or pride flags worn like a cape. We knew we were meant to be here. I knew I was meant to be there, but a moment of unease caught in my throat as I walked in, a voice from four years ago trying to choke out to me. She was scared. She had never been in such a place. Eventually, She subsided with a deep breath and the remembrance that I could be there, too.

Inside, there was a disco ball sending lightstreams dancing across my skin. My eyes flitted across the crowd, noticing girls kissing girls and boys kissing boys and not an ounce of fear in their hearts. I remember looking forward to a time in my life that I could feel so out and proud and safe, where my mom accepts me and I wouldn’t have to worry about caring what family members see on my social media. That night was the closest I came to that goal since I came out.

Sticker sheets of holographic stars and smiley faces were being passed around loudly and joyously. I took one of each (yellow star, green smiley) and had one of my friends place them on the apples of my cheeks to catch the light of the disco ball with every rotation. Later, when the night was done, I re-pasted the stickers to the back of my phone case until their manufactured sheen inevitably softened and disintegrated over time. The memories from inside that venue, however, are still bright and forever shiny.

As we left the concert, we were confronted with the reality of the city. Each of us in brightly coloured makeup and nearly outlandish outfits standing out like sore thumbs on the public transit, neon bruises in the greater and greyer population. I was objectively one of the more covered ones, so I took it upon myself to link elbows with my bare-legged friends and serve as a barrier between them and any passerby.

I’ve been chasing the feeling I found inside that venue ever since. I have yet to find it. The first “gay” bar I went to in Victoria has since switched over ownership and has become a rather dangerous space. Paparazzi Nightclub used to be branded as a strictly queer space but with the change in ownership, the original values of the night club no longer are prioritized. Victoria still holds a handful of LGBTQ+-priority spaces— such as Vicious Poodle or Friends of Dorothy’s, both places with a lively roster of events at both brunch and cocktail hour— but they feel like an endangered species. We can never be confident that each night we attend isn’t our last. It’s too often that someone I know (often female-presenting) goes out and their drink is spiked or is hit on unwantedly by a man who can’t take a hint.

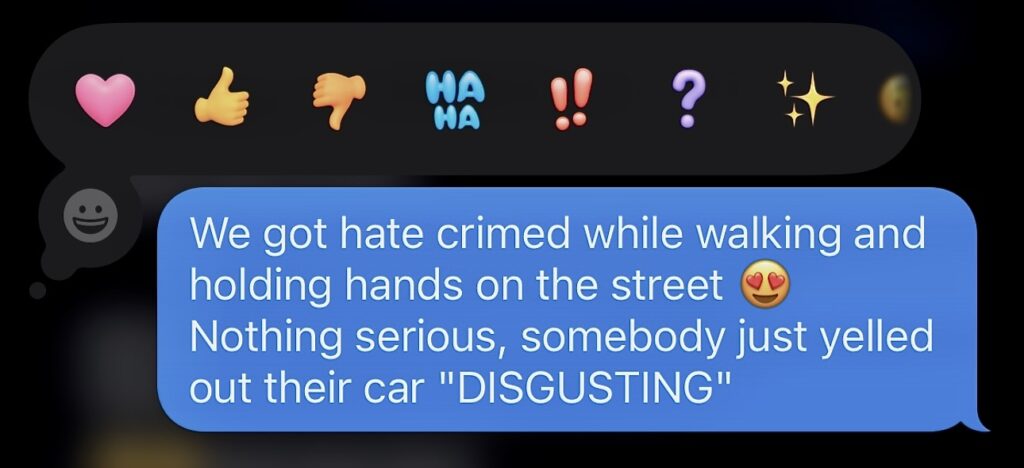

I’ve since become a once-a-month frequenter of Vicious Poodle and their rotation of events, from Drag Brunches (with excellent waffles and mimosas), to karaoke and bingo, to UHaul Nights. These events come close to the feeling of safety and joy I chase, but often are tainted by someone calling out their car window at my partner and I, holding hands as we walk to or from the bus stop on the nights we do get out.

A text sent by my partner to their two moms, November 2024. Photo: Piper Elliott

I acknowledge that when standing alone, I am less visibly queer than most. As far as I’m aware, it’s often only other queer people who see me, my thumb ring, my carabiner and all these little indicators. But in a collective, I radiate. I am seen with my non-binary partner and their fluidity and our holding hands. I am seen through my friends’ dyed hair or shaved heads or pronoun pins or ribbons and flags. In this collective, we are stronger together. Identity is built and shaped and curated through selective ring placement, cuffed jeans, keys-on-belt-loops, in our green carnations and violets.

Now, as enjoyable and as formative as that deeply queer crowded concert was for me, I wish it wasn’t a one-night-only, irreplaceable, non-recreatable space in which I had these realizations— that it is possible for me to feel safe in a space, that I do have a place of belonging, that there is a community that will uplift me alongside themselves. I wish there was more certainty in the stability of queer spaces, and if I’m really going to stretch, I wish there were more places that don’t have to be labelled and popularized as strictly queer places for someone like me to feel safe.

Again, I acknowledge that I am not the most visibly queer person when standing alone. I will likely never be targeted if I am standing on my own— at least with the way I currently present myself. But, assuring the preservation of distinctly queer spaces isn’t just for me and my ebb and flow along the various queer spectrums. This is on behalf of those who lift me up with them in their own more visible queerness. If they are not safe, neither am I. And if I am not safe, they most definitely aren’t. I realize this privilege of mine, appearing objectively more heteronormative in self-presentation than the next person, and although it’s a newer realization, I am learning to balance knowing that I have the ability to protect my friends in this way while simultaneously fearing for myself.

However, I am forced to recognize that I can’t do much in situations of greater danger. If the Vicious Poodle or Friends of Dorothy were to be closed tomorrow, I’d be useless standing alone. And sometimes, when watching political happenings unfold in our neighbouring country, it is easy to think that we are better off in Canada. But the truth is, we have had our own brutal LGBTQ+ journey and we still have quite a ways to go.

In preparation for the 1976 Summer Olympics, Montreal Police were on a mission to “clean up” the city from February 1975 to June 1976, resulting in raids at well-known bathhouses and gay/lesbian bars in the gay subsect of Montreal on Stanley Street. “For a lot of men in Montreal, their first experience of the great Olympic ‘clean-up’ was the sight of a policeman’s axe crashing through the door of their room at the baths,” said The Body Politic, a Toronto-based, queer, activism magazine published from 1971 to 1987. These raids resulted in more than 300 LGBTQ+ individuals and allies combined for one of the largest demonstrations of its time.

It wasn’t long until a much more impressive count of protestors (2000!) gathered. In 1977, 50 Montreal police officers, with bulletproof vests and guns drawn, raided two gay bars on Stanley St. 146 patrons were arrested, tallying the biggest mass arrest since the “War Measures Act” was announced. The crowd gathered the day following these Montreal Raids, while police “rode their motorcycles into the crowd, clubbing protestors, who in turn threw beer bottles at the police”.

For a lot of men in Montreal, their first experience of the great Olympic ‘clean-up’ was the sight of a policeman’s axe crashing through the door of their room at the baths

The Body Politic – Issue No. 25, August ’76

Four years later, the number of arrestees nearly doubled. Nearly 300 men were arrested in 1981, as a result of “Operation Soap”— a series of coordinated raids involving 200 police officers and four bathhouses in downtown Toronto. Operation Soap joined the list as one of Canada’s largest mass arrests entirely.

More recently, in September 2000, for an hour and a half, five male officers in civilian (“normal”) clothes walked though all four levels of a bathhouse with over 350 attendees at a special semi-annual event called “Pussy Palace”, under the premise of inspecting and searching for liquor licence violations. An article in Antipode Journal describes it as a rather calm investigation, deeply invasive, but objectively calm. “They observed half-naked women in the pool, sauna, whirlpool, and showers. They knocked on closed doors. They questioned bathhouse participants. They recorded the names and addresses of the organizers, and then, departed.”

The aftermath of this event didn’t come to light until two weeks later, when six charges were made against two volunteer organizers, where they would have faced a year in jail and fines up to $100,000 if convicted. The authors of the paper continue to describe the raid as “a deliberate crackdown on homosexual sex and nudity that was uncalled for given that relations between the local police and the gay community had been relatively incident free for over 15 years.”

Venues for active nudity and intimacy or nightlife and alcohol aside, Canada’s first and oldest surviving LGBTQ+ bookstore in North America, Glad Day (opened in 1970, Toronto) was raided in 1982, where employee Kevin Orr was charged with “possession of obscene material for purposes of resale.” In 1986, this time on the west coast, another bookstore was impacted for similar reasons. On December 8th, Canada Customs seized Vancouver bookstore Little Sister’s’ Christmas shipments. 59 titles were seized then, 19 additional titles were detained two days later, and by the end of the month, over 600 books destined for Little Sister’s shelves had been seized by Customs. Despite it all, Glad Day celebrated 50 years of “endurance and ability to adapt” in January 2019, and Little Sister’s is going on 41.

A photo taken at the Victoria Event Center at a January 2023 event, featuring local band Peanut Butter Telephone, with Christopher Atkins and Actual Human People. Photo: Kennedy Halwa

Now, a gay bar in Calgary received a termination of lease back in November of 2022, for the property owners to develop commercial space and an apartment complex on its grounds. The Backlot officially closed its doors this past July.

Even closer to home, was the closure of the Victoria Event Center this October. The VEC was a “cornerstone of the local arts community” for 21 years after opening in 2003, providing a venue with a third-place feel for art forms of all kinds to be showcased in front of a crowd and management that focused on inclusivity, diversity, and empowerment. The events I attended here felt like that concert last November, but it wasn’t a one-time event. I was lucky enough to attend several shows, ranging from lineups of local bands to drag performances, where I was able to find, know, and love an incredibly unique and vibrant community. It hasn’t been long enough since the “death” of the Victoria Event Centre for me to have truly come to terms with the loss, but the city moves on quickly. Less than two weeks after the closure of VEC, it was announced that Paparazzi Nightclub would be expanding into the space…

To me, the writing process and creation of this zine serves as a reflection. In queer joy, there is also a deep sense of melancholy. I often find this inevitable, and these feelings inseparable. I have yet to find the balance between feeling celebratory in the progress made and feeling the loss of time, knowing all that occurred before this point, feeling the weight of those who can’t join us in our jubilation today. In order to not become helplessly hopeless as a queer individual, I have no choice but to look at these stories and learn from the strength found in community. We have always been focused on uplifting each other. The loss of these spaces makes it difficult, but we will make our own spaces within the collective of ourselves. We cannot be removed from society. Our existence will continue to be known.

Written by Kennedy Halwa

Published 13 December 2024

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.