Keila’s article

So you’re feeling hopeless about the climate crisis? Me too.

Above photo by Ed Hawkins, climate scientist at the University of Readings courtesy of Wikimedia commons

In a world controlled by people who don’t prioritize sustainability and climate-change deniers, younger generations have the weight of a warming world on our shoulders. We are constantly reminded that on this trajectory, the world will be an inhospitable hellscape within our lifetimes. Personally, I don’t feel equipped to deal with this, especially in this political climate. I’m twenty-two, I’m exhausted and I’m numb. I have an education to get, rent to pay, a terrible job market to navigate, and slim prospects of ever owning a home. And I’m supposed to be the hope for the future? I don’t feel very hopeful. However, the last thing the world needs is for my generation to succumb to apathy, escapism, and hedonism. Come with me as I dig myself out of this hopelessness, by briefly recapping what I don’t need to tell you, followed by a review of the relevant psychological literature, and finally a critique of the public discourse around climate change and the accompanying anxiety.

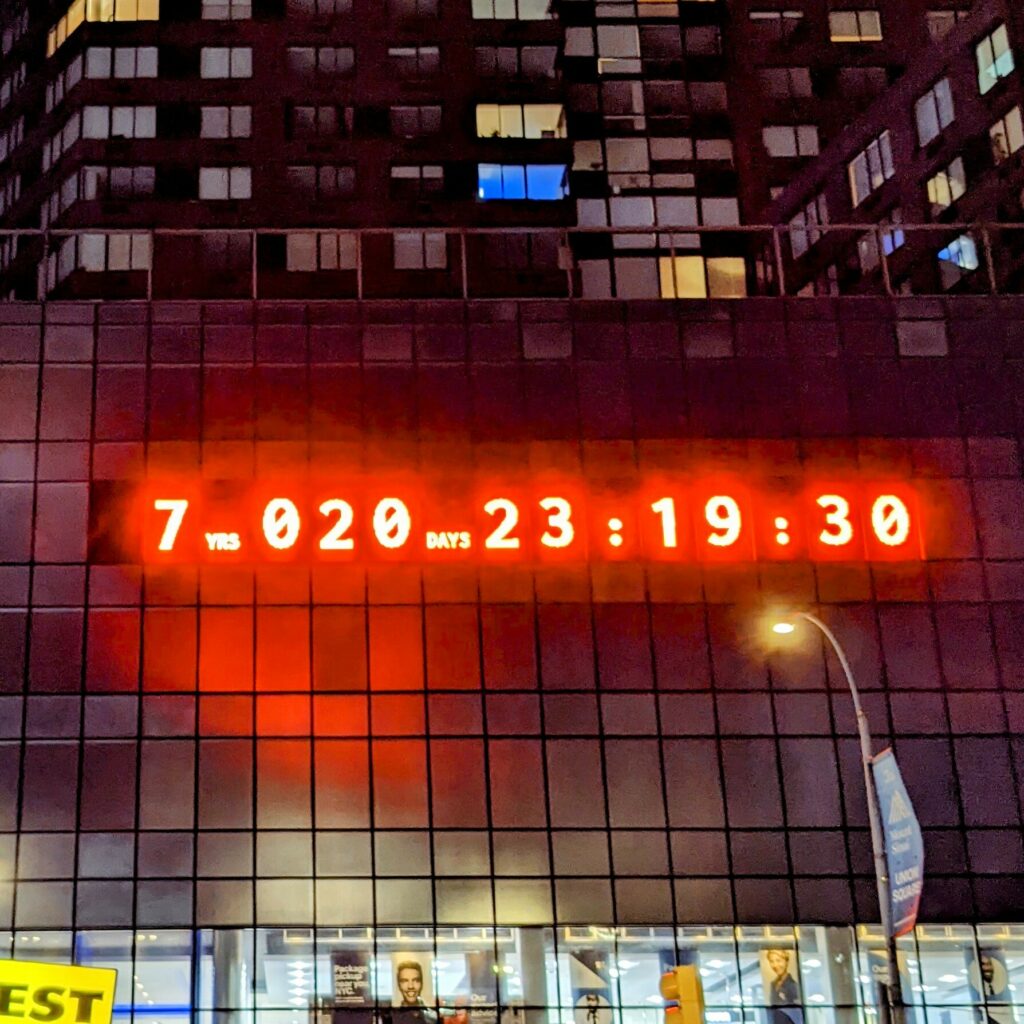

With the increasing effects of climate change being felt globally, I don’t need to tell you that in the grand scheme of things, we don’t have time. With the climate clock ticking down online and in Union Square, the pressure is palpable. I’m sure you felt the same sinking in your stomach as I did when you heard that in January 2024, the average temperature was 1.5 degrees warmer than pre-industrial times for 12 months straight, and that this happened faster than scientists thought it would, indicating that the bleak future that has been looming over our heads is closer at hand then we may have thought. You probably conjured up images of dying coral reefs, wildfires, and monster storms that are currently unfolding. If those facts didn’t jump to mind, other apocalyptic scenarios probably did. However, on a personal level, we have bills and inflated rent to pay, jobs to find, and expensive groceries to buy. Compared to these weekly and monthly obligations, solving the climate crisis, which is on a timescale of years, continually slips through the cracks. Human time and energy is a finite resource, so how are we going to allocate our mental, and emotional resources?

Psychologists define climate anxiety as how we perceive, dread, and fear the effects of climate change. It is an adaptive response to a real threat and is not a pathology. In line with negative emotions being important drivers of action, climate anxiety has been shown to occur in tandem with pro-environmental behavior. Maladaptive climate anxiety, on the other hand, can involve feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, and avoidance of the issue can cause distress that interferes with people’s daily functioning; and has been described as “chronic fear of ecological doom.” Gen Z and Gen Alpha will have more experiences of climate-change-related stressors in their lifetimes than current adults, and accordingly, studies have indicated higher levels of anxiety and concern about climate change amongst younger people.

This is precisely what Sarah Jaquette Ray tackles in her relatively short and accessible book A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet. She challenges “hope” as it is used in climate change discourse. Hope is often sought as a distraction from the gravity of the situation, so some climate activists have little patience for it. This sounds awful, but in the context of other discourses about climate change, I agree with it. Let me explain.

Jonathan Franzen, author of the 2019 New Yorker article “What if we stopped pretending” identifies a couple of potentially harmful discourses around the climate crisis. He points out that many articles imply the climate crisis “can be ‘solved’ if we summon the collective will”. Ray echoes this observation with one of her own, writing “Nearly all the usual suspects seem to have received a memo that they should add a spoonful of sugar to help the apocalypse go down.” Further, Franzen calls out that denial of the current situation is entrenched in progressive politics in addition to overt conservative climate denial. The Green New Deal, in the US, the guide for many renewable energy projects, is often characterized as our last chance at “stopping” climate change, which Frazen emphasizes is only theoretically possible. The language of “stopping” climate change implies that there is still time to prevent it, when multiple tipping points, “critical thresholds in a system that, when exceeded, can lead to significant change in the state of the system” according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), have been reached. Instead of building renewable energy systems that ironically destroy ecosystems, Franzen suggests shifting resources towards climate-change preparedness.

In my circles, it’s acknowledged that changing one’s lifestyle habits to be more eco-friendly is only a part of what’s needed to combat the climate crisis. In my friend group from high school, the argument that individuals can’t solve systemic issues was oft repeated. While this is true, I’ve seen this argument, combined with black-and-white thinking, make people give up entirely on individual lifestyle changes; give up on voting with their dollars; sometimes give up on voting in elections; and give in to nihilism. Their rationale is essentially “The world is going to end horribly no matter what I do, so might as well enjoy life while it lasts.” I’ll admit, I have thought this too. As Ray writes, “We doubt that not buying pens will save turtles”. When people aren’t talking about the latest climate-change-induced catastrophe or a harbinger of one, people don’t want to think about the climate crisis, it’s sad; I don’t want to feel sad. However, as Crandon et al. write, “silence communicates that discussing the topic is unnecessary or futile.” This is a conundrum that requires, on a personal level, managing one’s own emotional energy, a task that is difficult when there is money to be made from anyone’s sustained attention.

So we’re stuck waiting, hoping, for one or two great heroes in the younger generation, a genius invention or huge leaps in scientific thought, when that’s not realistic. As Joe Hanson, molecular biologist and host of PBS’s YouTube channel Get Smart, explains, that’s not how invention happens. Science is a slow, messy, and crucially, collaborative process. We have to get these ideas of singular geniuses out of our heads because they’re not serving us. At one of his talks, the ecophilosopher Derrick Jensen was asked by an audience member what hope was. He turned the question back to the audience, and collectively they defined hope as “a longing for a future condition over which you have no agency; it means you are essentially powerless”. This helps me understand why both Ray and Franzen argue against “hope”. As easy as it would be to say that I’m powerless, and continue hoping for a deus ex machina for the climate crisis, narrativizing the story of my life, or the story of humanity this way is not going to help either of them.

“If you persist in believing that catastrophe can be averted, you commit yourself to tackling a problem so immense that it needs to be everyone’s overriding priority forever.”

Jonathan Franzen

Franzen writes, “If you persist in believing that catastrophe can be averted, you commit yourself to tackling a problem so immense that it needs to be everyone’s overriding priority forever.” This calls to mind all sorts of dystopian ways of deciding who gets to survive and who doesn’t. It must be noted that as a white person with generational wealth living in North America, I have financial resources that can be transformed into resources to cope with climate change while others don’t. People in the “Majority World” as Crandon and colleagues call it, are already disproportionately affected by the climate crisis. The former chairman of the G-77, an organization of low-income nations, Lumumba Di-Aping, tearfully called a global goal of 2 degrees Celsius “a suicide pact” at the 2009 UN climate talks. If climate trumps (no pun intended) every other issue, then who will survive on a demographic scale is already decided. Can you feel my Green(white) Guilt about being complicit in causing suffering? Well, as racialized activists remind us, my guilt doesn’t help unless I do something about it.

Echoing this cue, Ray argues against calls for “empathy” in these situations. Mirroring the psychological literature on maladaptive climate anxiety, she writes “hyper-empathy about others’ suffering can get in the way of our ability to function” and “rarely changes the circumstances of those who suffer”. Ray, for all her rallying, acknowledges that it is difficult to do much about the climate crisis if you’re frozen or burnt out. When one of her students joked about being in the “baking stage” of environmental grief, Ray realized that her student was onto something. Her student bringing her baked goods to class was basically saying, “Let me remind you why I’m doing all this.” Thus, following anarchist feminist philosophy, the future we are working towards must protect pleasure, she argues. But Ray advises “Do not defer [pleasure] until the revolution is over”. Actions that recharge us and build resilience are vital to sustaining ourselves, so we can keep doing the work of climate justice. Ray reasons that “preserving yourself for a lifetime of thriving in a climate-changed world” is the whole point.

“… you have the capacity and power to do something, including the most important task—preserving yourself for a lifetime of thriving in a climate-changed world: that’s the point.”

Sarah Jaquette Ray, A Field Guide to Climate Anxiety: How to Keep Your Cool on a Warming Planet, p. 122.

That may sound selfish, but I’ll return to rhetoric I previously admonished as a balm for my overwhelm: individuals can’t solve systemic issues… on their own. This is why countless writers, journalists, and activists call for collective solutions. Psychological research on climate anxiety backs up this call. Crandon and coauthors suggest that collective action at community and global levels might help to share the psychological burden.

Like the climate crisis, any solution for maladaptive climate anxiety must be multi-pronged. There seem to be three types of strategies: changes in how we talk about the climate crisis, policy considerations, and individual actions.

In circles where the climate crisis may be in question, discussing the effects of climate change on a local level rather than a larger scale, to reduce polarization. For example, shifting toward climate emergency preparedness, as Franzen advocates, is achievable at a local level. Further, reframing climate issues as a matter of health, makes the climate crisis a personal concern for everyone and places it firmly in everyday territory, not as some far-off to-do. In keeping with the everyday, people care about the places close to them, so asking people about changes in the places they hold dear, may be a way to facilitate discussion in politically polarized contexts.

As for policy, the authors of a review article on climate anxiety urge policymakers to listen to youth and engage with them as “key stakeholders in policy issues.” Further, they advocate for education that is geared towards action, in an effort to give youth a sense of agency where they might feel powerless. Community, as opposed to lone geniuses, is an important aspect of this action-oriented education, so that young people don’t feel like they are in this alone.

Action has been called an ‘antidote’ for climate anxiety, by psychologists. However, they caution that framing climate change as a doomsday might contribute to despair and hopelessness. Ooops, I guess it’s too late to change the background of the website. But to more senior generations: I know that as individuals, you have also been subject to hard-to-change systemic issues; but I need you to feel at least some of what I am feeling. That’s the point of the climate clock. It came into existence because of youth activism, because of negative emotions, and because “Greta [wanted] a clock.” The clock is a piece of activism, and activism is supposed to make you feel something; and in turn, make you do something. As scary as the clock may look on its face, the organizers of the climate clock assert that “we will never run out of time to act in defense of people and the planet.”

“We will never run out of time to act in defense of people and the planet.”

the organizers of the climate clock

I’ll take that to mean that even when it seems like the world is too far gone, you are always powerful enough to do something about climate change, even in the smallest of ways. Near the end of his article, Franzen asserts that small, seemingly unrelated actions can be considered climate action. “Any movement toward a more just and civil society can now be considered meaningful climate action,” he writes, including securing fair elections, combating wealth inequality and misinformation on social media as forms of climate action. Local projects like Community Cabbage, who divert food that would be wasted to increase student food security, are climate action. I’m aware of the irony, but I’d like to close with “a spoonful of sugar”: you’re not alone in this. The widespreadness of (adaptive) climate anxiety, and its association with pro-environmental behaviours, indicates the potential for action. So, get in on the action.

Written By Keila Brock

Published 13 December 2024

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.